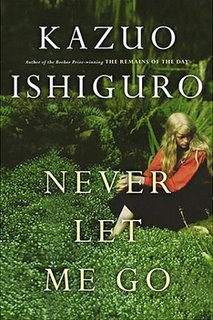

But that was more than a decade ago, and on Sunday, I spent my day reading Kazuo Ishiguro's Never Let Me Go, another story about the morality of a group of kids at an elite prep school, but one with a

chillier heart and big ideas in mind. It's clear from the book's first pages that something is askew. The narrator, Kathy H., is a nurse of unspecified expertise, looking back on her education at a school called Halisham. After vague preliminaries about Kath's unusually long professional tenure, she describes a day from pre-adolescence, in which she and her friend Ruth watch a classmate named Tommy lose his temper in a soccer game.

chillier heart and big ideas in mind. It's clear from the book's first pages that something is askew. The narrator, Kathy H., is a nurse of unspecified expertise, looking back on her education at a school called Halisham. After vague preliminaries about Kath's unusually long professional tenure, she describes a day from pre-adolescence, in which she and her friend Ruth watch a classmate named Tommy lose his temper in a soccer game.This is a book about Halisham, and a love story about Kathy, Ruth and Tommy. Ishiguro hints that something is wrong with their world -- from Kathy's vague allusions about undefined carers and donors, and her oddly detached narrative voice. There is plenty of emotional repression, yes, but something larger is at work, and only as the story unfolds does its tragedy incrementally become clearer. A novel about moments that haunt you when you're young expands into bigger themes, about science and love and art and free will.

Some reviewers have described the book as science fiction and others as a cautionary tale, and though I don't think either label gets the job done, they'll do for the sake of allusion. But unlike many reviewers, I don't think of the book as a genre piece, or anything close to pulp. Its views about science are to be taken seriously, but I agree with Michiko Kakutani's description of the book as fundamentally "an oblique and elegiac meditation on mortality and lost innocence: a portrait of adolescence as that hinge moment in life when self-knowledge brin

gs intimations of one's destiny, when the shedding of childhood dreams can lead to disillusionment, rebellion, newfound resolve or an ambivalent acceptance of a preordained fate."

gs intimations of one's destiny, when the shedding of childhood dreams can lead to disillusionment, rebellion, newfound resolve or an ambivalent acceptance of a preordained fate."Conservative commentors seem to view the book as a warning against unrestrained science. This is a plausible interpretation, but it didn't occur to me as I read it. Instead, I viewed it as having E.M. Forster's soul in Alduous Huxley's body. In much the way that the mafia setting of The Sopranos crystallizes family conflicts that would otherwise seem routine, the genre undertones of Never Let Me Go permit Ishiguro to shed shopworn adolescent baggage and focus his narrative on what matters.

I don't want to say any more about the plot than that. I came into this book without any background -- no Amazon reviews or professional reviews -- and it's best experienced that way. My lack of preparation allowed me to learn about the characters' world alongside them. If I'd known more, I might have loved this book less. I read all 290 pages in a day, staying up until 3 a.m. to finish, at which point I re-read the first chapter and responded in a way appropriate to a five-year-old who's watching Bambi for the first time: a blubbering baby breakdown.

Time Magazine selected Never Let Me Go as one of the 100 best English-language novels since 1923, which sounds about right. In story, narration, and clarity, the book stands on par with Ian McEwan's Atonement. Between McEwan, Ishiguro and Zadie Smith, the Brits are teaching their American counterparts some knockout lessons in how to write a novel. Why the U.S. hasn't yet produced a young-ish writer in the caliber of Smith and Ishiguro, I'll think about some other time.

2 comments:

I disagreed with the positive reviews on Ishiguro's latest offering. When you set up a concept as futuristic and loaded as cloning it makes demands on you that a more traditional plot does not. Ishiguro dissapoints in many ways. The plot and concept of the novel are strong--what would the lives of people created as clones for organ donation be like?--but he fails to address most of the salient issues that this topic demands. For one thing, the story is told first person by one character all the way through and the tone is extremely conversational, as if this character is knowingly telling the story to another clone, but that clone is not easily identified with as the reader--I'm not a clone and know nothing of their world--and that tone bogs the story down in a slightly annoying long-winded style that does nothing much to characterizatize the speaker. The narrator seems unbelievably naïve--which may be okay given her sheltered environment, but then it would seem to demand that as she enters the real world her naivete would fall way, though it never really seems to. More troubling Ishiguro doesn't address any of the real issues here. Number one, how does such a cloning/donation program get started? It is stated that no one in the public really asks wehre these organs come from, but that seems hard to imagine. Is it a secre conspiracy in the gov't? And number two, why wouldn't anyone ever try to escape the life? If they have their own living quarters, a car, etc, why not break away? How exactly are they controlled or trapped? Are they tattooed? Labeled? Deprived of work papers? These people seem to go willingly to their fate as donors, and yet there is no attept to explore why they do so so willingly--in fact they are kept in the dark as to the real hard truths about their life and their purpose for tmost of their childhood, so early brainwashing would not account for this compliance. And even if they are trapped with tattoos or work permits, why not try to fight back with the internet? Or a publicity campaign? There is strength in numbers, and these people make no attempt to even buck the system. Hard to imagine. Number three, what are these people donating without dying? I guess part of a liver, one lung and one kidney would work, but what else? You can't give away your heart--Ishiguro fails to face head on the ugliness of such a system, so his novel seems precious and underminagined to me.

Also, Ishiguro sets up plot points he fails to address--for example, what is special about the art that Ruth or Kathy produce? If Tommy is so much a failure in this regard, what are the other children producing? And if Madame and Miss Emily are so concerned about changing the system, why would they raise these kids and keep them in the dark rather than fight the system and reveal its horrors directly? Developing the children's self-esteem and artistic side only to see them later killed seems even crueler than purposely brainwashing them to see themselves as objects.

While these may at first glance seem like I'm trying to write his novel for him, truly these are the questions that he must consider given his own premise. Not to do so is a failure of fiction's main purpose--to create a coherent world in which an "experienced truth" (Flannery O'Connor) can be put across.

Ah! Thanks for the incredibly thoughtful and detailed comment, but you let out all of the plot twists that I was trying to avoid.

We obviously have two very different readings of what this book is about and what it's trying to argue. I doubt that I'll be able to persuade you, so maybe this isn't an argument against what you're writing so much as an alternative proposal for how to read the novel. As I said in my review, I didn't view this book as a genre piece or a cautionary tale about science, while you apparently were more inclined in that direction.

But I'll address your arguments piece by piece:

For one thing, the story is told first person by one character all the way through and the tone is extremely conversational, as if this character is knowingly telling the story to another clone, but that clone is not easily identified with as the reader--I'm not a clone and know nothing of their world--and that tone bogs the story down in a slightly annoying long-winded style that does nothing much to characterizatize the speaker.

I didn't share this reaction. I thought that Kath's narrative voice was highly persuasive and didn't find the tone remotely long-winded. If anything, it was spare and allusive. To the Lighthouse came to mind in the way that some of the most startling and heartbreaking revelations came about only by reference. To the extent that you think the story was addressed to another clone in her position, that was part of the mystery and atmosphere of the book.

The narrator seems unbelievably naïve--which may be okay given her sheltered environment, but then it would seem to demand that as she enters the real world her naivete would fall way, though it never really seems to. ... And number two, why wouldn't anyone ever try to escape the life? If they have their own living quarters, a car, etc, why not break away? How exactly are they controlled or trapped? Are they tattooed? Labeled? Deprived of work papers? These people seem to go willingly to their fate as donors, and yet there is no attept to explore why they do so so willingly--in fact they are kept in the dark as to the real hard truths about their life and their purpose for tmost of their childhood, so early brainwashing would not account for this compliance. And even if they are trapped with tattoos or work permits, why not try to fight back with the internet? Or a publicity campaign? There is strength in numbers, and these people make no attempt to even buck the system. Hard to imagine.

There was nothing that forced them to confront their worldview. And why would we as readers want easy answers for why they didn't try to escape? This isn't Minority Report. I had the same question -- on the day that Kath and Tommy are in Norfolk looking for the tape, why didn't they resolve to escape or confess their feelings? Why wasn't their a moment earlier in life when Kath and Tommy forthrightly addressed their feelings? Why was Ruth's conduct so destructively passive aggressive, and why was Kath so willing to accede to it? These aren't plot twists that demand answers from the writer -- they're the kind of open-ended questions that make a great novel a great novel. If you're looking at this as a genre piece that's making a statement about society, your questions make sense. But I don't think that's what this book is. I think it was a meditation on individualism and personality. Kath and the donors don't question their fates because they simply lack the tools to do so. Thinking of this in terms of blame or rebellion is unconstructive -- it would be like reading Gilead and wondering why the narrator is a Christian and incapable of rejecting Christianity. People have worldviews, some constructive and healthy, some repressive and destructive. That Kath et al. were raised in such a highly conditioned Pavlovian environment doesn't disrupt the book's credibility. I think, instead, that Ishiguro is heightening a metaphor for the kind of conditioning that we all grow up with -- a blindness that keeps people from questioning assigned roles and responsibilities, from questioning injustices in their own lives and in the lives of other people, from comfortable self-expression.

Number three, what are these people donating without dying? I guess part of a liver, one lung and one kidney would work, but what else? You can't give away your heart--Ishiguro fails to face head on the ugliness of such a system, so his novel seems precious and underminagined to me.

Personally, I find this question irrelevant. I wondered the same thing, but can't imagine how it would have been strengthened by specifying whether Tommy had donated a kidney or his liver. It would have been a distraction. Ishiguro knew what to include and what to leave out, and he did it for a reason.

Also, Ishiguro sets up plot points he fails to address--for example, what is special about the art that Ruth or Kathy produce? If Tommy is so much a failure in this regard, what are the other children producing? And if Madame and Miss Emily are so concerned about changing the system, why would they raise these kids and keep them in the dark rather than fight the system and reveal its horrors directly? Developing the children's self-esteem and artistic side only to see them later killed seems even crueler than purposely brainwashing them to see themselves as objects.

Aw, the last sentence is a great point. Why, in the end, did Madame and Miss Emily go to all of this trouble, and in the end was it crueler to give their students hope and a sense of normalcy, only for them to live out their lives as donors? Was that the ultimate cruelty? Maybe. But that's a question Ishiguro leaves us, not a flaw in his narrative. As far as the discussion of art goes, again, why does it matter? Maybe all they were doing was creating junk, and it was being praised in an arbitrary and random way. If they're living in a totalitarian bubble, is there any objective criteria for art, and do we have a way of believing or disbelieving that the other childrens' art was in any way superior to Tommy's? I guess we know at the end that Tommy had opted out of this system -- one of the only small acts of rebellion in the book -- but as to whether there was any objective quality to the ostensibly successful art, I think your questions are the answers. The students did as they were told; they craved praise; they craved some kind of larger meaning and connection to the outside; and what was important in the book was their processes and reactions, not the art itself.

Not to do so is a failure of fiction's main purpose--to create a coherent world in which an "experienced truth" (Flannery O'Connor) can be put across.

Obviously, I couldn't disagree more that the novel failed to do this. I think you're treating allusions and questions as indications of failure. The book would reflect "experienced truth" far less if it was a whiz-bang thriller where donors led a rebellion and coordinated activities through the Internet. That's a science fiction parable. That is not this book. That's a much weaker book.

Post a Comment